Sofia Gubaidulina Exclusive Interview: March 27, 2012

On Friday, March 16, 2012, Classical Archives Artistic Director Nolan Gasser received written responses to a set of questions sent a few weeks earlier to the renowned Russian composer Sofia Gubaidulina – who recently celebrated her 80th birthday, and whose works have been increasingly recorded and performed around the world. The music of Ms. Gubaidulina is marked by adventurous techniques and sonorities, yet underlined by intense religious feeling as well as profound, and often complex philosophical and psychological principles – such as is discerned in her responses here. She is the recipient of numerous awards and honors, and is widely seen as among the most creative and important composers of our day. This is a unique scenario for a Classical Archives interview, but one that is highly valued, as Ms. Gubaidulina rarely gives interviews: she lives in relative solitude in a small village near Hamburg, Germany, owns no computer, and speaks no English; as such, we are grateful for the valiant efforts of our own musical scout in Russia, Leila Yangurazova, who initiated a network of colleagues to translate and relay our questions and then to retrieve and translate her responses. As will be seen, these responses are highly literate and aesthetic in nature, and reveal the mind of a most accomplished creator. Don’t miss this fascinating and important interview!

“To me ‘aesthetic’ is only the top layer of the artistic phenomenon; this layer is visible, perceivable, traceable. But there is also a deeper layer: the layer that raises consciousness to its origins, to its fundamental sources. This layer may not be perceptible – and then it is accessible only to our imagination.”

– Sofia Gubaidulina

Loading, please wait...

Loading, please wait...

Nolan Gasser: Sofia Gubaidulina, welcome to Classical Archives. Allow me to begin by congratulating you on the many concerts held worldwide commemorating your 80th birthday! Let’s begin with the origins of this rich and varied style: your early years as a “radical” in the eyes of Soviet music authorities and the encouragement you received from no less than Shostakovich have been much discussed. Less clear to me are the specific influences upon your progressive musical tendencies. You’ve spoken of your early admiration of Webern, but can you talk about some of the other, more immediate influences in your formative years that spawned and informed the more experimental and “modernist” approaches you came to embrace, in terms of sound production, tuning, musical narrative, etc.?

Sofia Gubaidulina: Neither the word "progressive" nor the word "style" have ever meant too much in my life. Categories like these were almost always overshadowed by a completely different concern: namely, the truth of my own psychological state, and the question of whether I could ever come close to that of my inner nature and realize this truth in my compositions – that is, through the aural medium. The word “progressive”, from my point of view, can hardly be applied to art. The word “style”, although being very attractive, also contains some risks – exaggerated attention to it leads to the fact that aesthetic judgment begins to prevail over substance.

To me “aesthetic” is only the top layer of the artistic phenomenon; this layer is visible, perceivable, traceable. But there is also a deeper layer: the layer that raises consciousness to its origins, to its fundamental sources. This layer may not be perceptible – and then it is accessible only to our imagination. But this is precisely the most important reason for art to exist. It is this layer of consciousness, or rather sub-consciousness – it’s active state – that at times enables a person to reach the realm of “super-consciousness”. The game of consciousness and sub-consciousness creates new entities that don’t exist in everyday life; they are beyond the state of materiality. The art of music makes it possible to get closer – to touch these entities through an audible phrase, rhythm, and form. Devotees of pure style can come close to these entities, but they may never reach them. On the other hand, the true representatives of the [musical] art fully realized this tendency – with Johann Sebastian Bach and Josquin des Prés approaching this identity most closely.

Another aspect of your question is the issue of influences on the artist during the years of his or her formation. When asking this question, the imitation of a particular phenomenon – texture, intonation, or rhythmic features – is usually meant. But for me, I always understand the question differently: what underlying principles were important for me in my youth, and what personalities? For me, the personalities were J.S. Bach, Anton Webern, and Dmitri Shostakovich. In my works you will find no external physical resemblance to the works of these composers. Instead, it was really their dramatic effect: with Webern, the structural purity of his music; with Shostakovich, the tragic essence of his music; and with J.S. Bach, a unique mixture of structural ingenuity with the fiery substance of intuition. These principles have always been an unattainable ideal for me.

NG: One facet of your early career that played a major role in establishing your name, as well as developing your musical style, was your work with the folk-improv group Astreja in the mid-1970s. Can you share a few of the principle ways in which this activity opened unexpected vistas or gave you insight into the particular path you wanted to pursue as a composer?

SG: The experience of Astreja was a great treasure for me. Making music is not deciphering a written text, or creating its mere reproduction; instead, it is a spontaneous elicitation of sound fantasy, freed from all things external. It is oral speech in contradiction to writing. It is worth mentioning that in this group such common instruments as piano, violin, or cello were forbidden – because frozen, learned passages, cues, or phrases could unwantingly break through into the “speech”.

By contrast, there were many sounding objects and tools unfamiliar to us – that is, not those that we commonly master. This promoted our ability to imagine a situation where there is no tradition, no technology, where there is no established doctrine. We found ourselves in a situation like that which existed before the emergence of culture: the archaic state of sounding matter and the archaic state of mind, when the “source-word” might suddenly appear.

Basically, it wasn’t just playing music, but a sort of spiritual communion between us three musicians who used sounding matter for this kind of communication. This experience sometimes led me to a euphoric state of experiencing complete unity between my soul and sounding strings. Astreja was not a concert band, but a kind of experimental laboratory for music composition. However, sometimes we broke this private setting, inviting in the audience, but that was a rare exception. I must say that I have met many groups of this kind among young composers as well. It seems as if composers still have a longing for this primitive, archaic state of mind.

NG: Beyond the embrace of experimental techniques and sonorities in your music, another key facet of your compositional identity is your strong religious faith – which is manifest not only in your explicitly sacred vocal works, but also in many of your non-vocal works, notably your concerto-based cycle of Mass Propers and various chamber works dedicated to the themes of the Cross or the Last Judgment. Was Russian Orthodox worship a significant part of your life growing up, and can you articulate for us some of the ways in which your faith and your concept of “re-ligio” informs the decisions you make in compositional practice – even in works without an overt religious significance?

SG: My faith is my life, and it is my secret. The implementation of the religious requirements of the Spirit in compositional practice is a completely different type of indwelling of the soul in spirit, a type that differs significantly from that on the everyday level. For it is imagination, works of art, and art itself, which are different from nature. In art, there is the power of imagination, where I can move into an area that lies between the conscious and the unconscious, between dream and reality – to use [Carl] Jung's terminology.

As for the religious experiences of my life, these are my secrets; but I can share outward this “dream” to my neighbors through my art. How? By converting this experience into a purely musical phenomenon.

For example, Introitus [Concerto for Piano and Chamber Orchestra] explores the development of 4 states of melodic line – micro-chromatics, the chromatic scale, the diatonic scale, and the pentatonic scale – a metaphor for entry into the world of sonority, a kind of preparation for ministry in the nature of our time and space.

Therefore, the works of mine bearing ecclesiastical names do not pretend to be descriptions of church services; they are nothing but metaphors for the feeling that once motivated people to create these liturgical functions. In these works, I am outside of Doctrine; I am acting like a person who doesn’t know the life of the Church or its liturgy, but instead like one who feels a strong motivation to form, draw, and implement the essential desire of a religious individual – to recognize and actuate his or her vision of the meaning of service, a sense of sacrifice, the meaning of the invocation to the Supreme, the meaning of the symbol of the Cross, etc.

My religiosity in the composer's practice is a purely artistic phenomenon.

NG: Another pier, it seems, of your compositional praxis is your profound study and appreciation of numerology – and your embrace of numerical properties such as the Golden Ratio and the Fibbonaci sequence as sources of rhythmic and architectural elements. Indeed, you have discussed rhythm and duration as not mere surface elements but as “generating principles” of your music. Can you elaborate a bit on how number and rhythm function in your music, and why, for example, you see an unfortunate limitation in strict rhythmic formulas, such as Messiaen’s rhythmic modes?

SG: Indeed, I'm not ready to use certain elements of musical speech, including rhythm, to "generate" my compositions. On the contrary, I use the laws of the Golden Ratio not to create a live phrase from particular elements, but to limit the flow of sound, the flow that is always too powerful and too rich. Art always deals with this dichotomy: the intuitive flow and the structural requirements of the intellect.

However, since I do not want to "generate" living matter from elements, but on the contrary “generate” – that is, create, give birth to – the shape of things from living tissue, I find another opportunity to limit the flow of intuition: to subordinate the form of the sound stream to the law of the Golden Ratio [in short, a relationship in art or mathematics between two quantities, where the ratio of the sum of the quantities to the larger quantity is equal to the ratio of the larger quantity to the smaller one – i.e. where a + b / a = a / b].

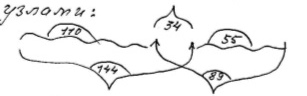

For example, I take not a measure, but a quarter note equal to 60 [beats per minute] for the metric unit of the musical flow. Herewith, it is very important for me to identify the “culmination zones”, which usually coincide with the so-called "architechtonic knots" [see Ms. Gubaidulina’s illustration below]:

This does not mean that “numerology” – that is, rhythmical formulae – “generates” the tissue; quite on the contrary. The tissue itself, the movement of the music [lit. “sound flow”] remains in the foreground; and the proportion of the rhythm to the form is the method by which I gain this restriction.

I must say that this type of composition requires much more time than did my previous approach – that is, with works prior to 1983. The “sound flow” is often unwilling to obey the law; you have to search for consent for a long time. And if it is reached, it is good luck. Of course the performed composition will not exactly fit my proportions. And I would not like to deprive the artist of freedom and initiative. But the path of this work still remains – and it is very important.

By the way, I have never said, nor could I have said, anything labeling Messiaen’s rhythmic style as a "deplorable restriction”, as has been cited. In fact, Messiaen’s technique involves the same restriction of “sound flow” that is important for me as well.

NG: In discussing your compositional process, you’ve spoken about the need to balance the implementation of a strongly worked-out structure on the one hand with the freedom of intuition on the other. Can you talk about how you ensure or attempt to bring this duality into equilibrium?

SG: This is the most profound drama appearing during the act of composing: intuition and the requirements of the intellect with its claim to implement “the law”. Here is a severe struggle every time: many insights, and a lot of frustration – the “law” and freewill are in constant struggle.

NG: Finally, much has been written about the criticism levied against you by the authorities, the so-called “Krennikov’s Seven” blacklisting, and so forth – which, according to some, may have been as much a blessing (in terms of gaining prominence in the West) as a curse. Can you share your view of how such conflicts impacted your aesthetic as well as your resolve as a composer?

SG: Yes, the above-mentioned opinion exists; it is unpleasant to me, of course. To face the question head-on, might it be the reason why my compositions are now performed? I am not sure, but I hope it is not the case. Though, at the very beginning of my career, it did play a role for some managers… But in my opinion this explanation could not have lasted so long – for almost 20 years! This political situation quickly changed, as you know.

As for “gaining prominence”, I don’t think I could be suspected of that – I live in solitude, and very modestly. None of my work has been performed by my own initiative. When asked how I feel in my solitude, I reply, "As the owner of a dovecote [a structure to hold doves or pigeons], I feed my birds. And they fly away where they like."

Below is the typed reproduction of Sofia Gubaidulina’s original hand-written Russian responses to our questions. The translation of these responses is our slight adaptation of that provided by Leila Yangurazova, with assistance from Alexander Suslin and Igor Kondorsky. Naturally, such translations – particularly of the abstract kind of discourse occasionally found here – is prone to some misunderstandings. If any of our readers uncovers a discrepancy, please let us know, and we will amend the translations at our earliest opportunity. To see the original hand-written answers, click on this link.

Дорогой мистер Нолан Гассер!

Поскольку Ваши вопросы затрагивают глубочайшие слои художественной жизни, я предпочла выделить из общего списка Ваших вопросов некоторые из них, чтобы детальнее углубиться в свои размышления. При этом мне пришлось отказаться от других вопросов. Прошу меня простить за это.

Вопрос 1 «…что оказало конкретное влияние на Ваш прогрессивный музыкальный стиль?»

Ни слово «прогрессивный», ни слово «стиль» не играли в моей жизни слишком большой роли. Эту мысль почти всегда затмевала совершенно другая озабоченность, а именно: правда моего личного психологического состояния и вопрос, смогу ли я хотя бы когда-нибудь приблизиться к этой моей сущности и осуществить эту правду в моем сочинении. То есть, через звучащую материю.

Слово «прогрессивный», с моей точки зрения, в применении к искусству весьма проблематично.

Слово «стиль», хотя и очень привлекательно, но содержит в себе некоторую опасность. Преувеличенное внимание к нему приводит к тому, что эстетическая оценка начинает превалировать над сущностью.

Для меня «эстетический» – это только верхний слой художественного явления. Слой видимый, ощущаемый, доступный анализу.

Но существует более глубокий слой. Слой, возводящий сознание к своему началу, к своим фундаментальным истокам. Этот слой может и не быть визуальным. И тогда он доступен только нашему воображению. Но именно он является важнейшей причиной, почему существует искусство.

Именно этот слой сознания, точнее подсознания, его активное состояние, позволяет человеку временами достигать сверх-сознания. Игра сознания и подсознания создает новые сущности, которых нет в обыденной жизни. Они – вне материи. Искусство музыки дает возможность приблизиться, дотронуться до этих сущностей через звучащую фразу, звучащий ритм, звучащую форму.

Представители чистого стиля могут приблизиться к этим сущностям. Но могут и не достигнуть этого.

В то время как представители художественных явлений, реализуемых вне этого стремления, т.е. стремления быть непременно чистыми стилистами (И это – J.S. Bach. И это - Josquin des Pré.), приближались к этой сущности.

Другой аспект Вашего вопроса – вопрос о влияниях на художника в годы формирования.

Когда задают этот вопрос, обычно имеют ввиду подражание тому или иному явлению (фактура, интонационные или ритмические особенности).

Я же всегда понимаю этот вопрос иначе: какие основополагающие принципы были важны для меня в период моей молодости. Какие личности.

И это были И.С. Бах, Антон Веберн и Дмитрий Шостакович

В моих сочинениях вы не найдете никакого внешнего, материального сходства с сочинениями этих композиторов.

Но это действительно сильнейшее влияние:

Веберн – структурная чистота.

Шостакович – трагическая суть.

И.С. Бах – уникальное объединение структурной изобретательности с огненной субстанцией интуиции.

Эти принципы были и остаются для меня недостижимым идеалом.

Вопрос 2. Относительно опыта музицирования в ансамбле «Астрея».

Этот опыт для меня был большой драгоценностью. Музицирование, которое не является расшифровкой записанного текста, его воспроизведением, а спонтанным, освобожденным от всего внешнего выявлением звуковой фантазии. Это – устная речь в отличие от письменной.

Интересно то, что в этой группе запрещены известные нам инструменты – фортепиано, скрипка, виолончель, поскольку через них могли бы в эту «речь» прорваться застывшие, выученные пассажи, реплики, фразы.

Зато перед нами – множество звучащих предметов и незнакомых нам инструментов (т.е. тех, которыми мы не владеем).

Это способствует тому, что мы имеем возможность вообразить себе ситуацию, где нет никакой традиции, нет никакой техники, нет никакой сложившейся доктрины.

Мы попадаем в ситуацию, которая находится до возникновения культуры: архаическое состояние звучащей материи и архаическое состояние сознания, когда может неожиданно явиться пра-слово.

По-существу, это даже не музицирование, а духовное общение трех персон, которые используют для этого общения звучащую материю.

Этот опыт иногда приводил меня к восторженному состоянию полной идентичности моей души и звучащей струны.

«Астрея» - это не концертная группа, а как бы экспериментальная лаборатория для сочинения музыки. (Правда, иногда мы нарушали эту установку, приглашая слушателей, но это исключение.)

Надо сказать, что я встречала множество таких групп среди композиторской молодежи. Видимо у сочинителей есть какая-то тоска по этому первобытному, архаическому состоянию души.

Вопрос 3. «Каким образом Ваша вера и Ваше понимание религиозности осуществляется в Вашей композиторской практике?»

Моя вера – это моя жизнь. И это – моя тайна.

Осуществление же религиозных требований духа в композиторской практике – это совсем иной тип пребывания души в духе; тип, который существенно отличается от пребывания на житейском уровне. Ибо это – воображение, художество, искусство, оно отличается от естества. Здесь я могу силой воображения перенестись в ту область, которая находится между бессознательным и сознательным, между сном и реальностью (если использовать лексику Юнга). И если религиозное переживание в моей жизни – это моя тайна, и ее я не могу выдать вовне, то в искусстве, в художестве этот «сон» я могу рассказать ближнему. Но как? – с помощью превращения этого переживания в чисто музыкальное явление. Например, ‘Introitus’: развитие 4-х состояний звуковых линий – микрохроматика, хроматика, диатоника, пентатоника – это метафора вхождения в мир сонорики, т.е. действительное приготовление к служению в свойственном нашему времени пространстве.

Поэтому сочинения, имеющие церковные названия, не претендуют на то, чтобы быть описанием церковных богослужений. Они – только метафоры того чувства, которое когда-то побудило человека создать эти богослужебные действа.

Здесь я нахожусь вне доктрины. Я нахожусь в состоянии человека, который еще не знает, что такое церковная жизнь и ее установления. Но чувствует глубокую необходимость сформовать, оформить, реализовать сущностное желание религиозного человека, ─ осознать и привести в действие свое видение смысла служения, смысла жертвоприношения, смысла взывания к Высшему, смысла символа креста, и т.д.

Моя религиозность в композиторской практике – это чисто художественное явление.

Вопрос 4. «Используется ли Вами нумерология, связанная с соотношениями золотого сечения, как генерирующий принцип?»

Нет. Я не готова какие-то элементы музыкальной речи, в том числе и ритм, использовать для «генерирования». Наоборот, законы золотого я использую не для того, чтобы из каких-то элементов создать живую фразу, а для ограничения звукового потока, который всегда слишком мощный и слишком богатый.

Искусство всегда имеет дело с этими противоположностями: интуитивный поток т структурные требования интеллекта.

Но, поскольку я не хочу живую материю «генерировать» из элементов, а наоборот, из живой ткани «генерировать» (создавать, рождать) форму вещи, то я нахожу другую возможность ограничить интуитивный поток: подчинить форму этого звукового потока закону золотого сечения.

За метрическую единицу потока я принимаю не такт, а одну четверть, равную 60.

При этом очень важно для меня выявление кульминационных зон, которые обычно совпадают с так называемыми «архитектоническими узлами»:

Но это не значит, что «нумерология», какие-то ритмические формулы «генерируют» ткань. Наоборот. Приоритетный всегда остается сама ткань, звуковой поток. А пропорции ритма формы – способ ограничения.

Надо сказать, что этот тип сочинительства требует гораздо бóльшего времени, чем мой предыдущий опыт (до 1983 года). Звуковой поток очень часто не желает починиться закону. Приходится долго искать согласия. Но если оно достигнуто, то это – удача.

Конечно, исполненное сочинение не будет точно соответствовать моим пропорциям. И я не хотела бы лишать исполнителя свободы и инициативы. Но след от этой работы все же остается. И это уже очень важно.

Кстати, я никогда не говорила и не могла говорить о «прискорбном» ограничении ритмического стиля Мессиана. Как раз у Мессиана его техника является таким же ограничением потока, который и для меня очень важен.

Вопрос 5. «Как Вы уравновешиваете тщательно разработанную конструкцию и спонтанное вдохновение?»

Это самая глубокая драма при сочинении: интуиция и требования интеллекта со своей претензией осуществить закон. Здесь – каждый раз суровая борьба. Множество озарений, множество разочарований.

Борются: закон и своеволие.

Вопрос 6. «Существует мнение, что Ваше имя в черном списке «Хренниковской семерки», ─ это не только проклятие, но и благословение (в смысле стяжания известности на Западе)».

Да, это мнение существует. Это мне, конечно, неприятно. Но, если посмотреть правде в глаза, то, может быть, действительно мои сочинения звучат по этой причине? Не знаю. Но надеюсь, что это не так. Может быть, в самом начале для некоторых менеджеров это и играло какую-то роль.

Но не думаю, что это могло продолжаться столь долго. Почти 20 лет. Ведь эта политическая ситуация быстро изменилась.

Относительно «стяжания известности»:

Не думаю, что меня в этом можно было бы заподозрить. Я живу уединенно. Очень скромно. Ни одно исполнение моих сочинений не произошло по моей собственной инициативе.

Когда меня спрашивают, как я чувствую себя в своем уединении, то я отвечаю: «Как хозяин голубятни. Кормлю своих птичек. А они разлетаются, куда хотят».